Toni Cade Bambara Remembered

By Guest Contributor on November 26, 2014By Donald P. Stone

Editors’ Note: This previously unpublished essay was originally written in 2001.

I met Toni Cade Bambara in the late sixties. She was visiting A. B. and Karen Spellman at their Fair Street home in Atlanta. Toni and A. B. were colleagues at Rutgers University. Previously, in the mid-sixties, A. B. had come South to Atlanta on a poetry reading tour with some other poets. A. B. and I connected, and we hung out a lot with other members of the Student NonViolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and consequently, some SNCC sisters had decreed that he would never return to his former social and political environment in Greenwich Village in New York. And he never did. Numerous Black artists were dealing with the question of their social consciousness. Remember…it is the mid-twentieth century, and a state-sanctioned terror in the South confronts African Americans; the Confederate Counter-revolution rules. Blacks are routinely murdered with impunity and have no democratic rights. We’ve got a big fight on our hands, and we’re in the midst of it.

How does the “conscious artist” respond to these circumstances? We were learning that our social consciousness was developing out of our social being (our social activity). By engaging the Movement, we were awhirl in the social and political currents raging all about us. To defeat the racist terror of the south, in particular, and to move this entire country towards a more democratic republic were daunting tasks, and African American artist had to participate; had to be engaged. A fundamental question was: How could our culture, our art, be relevant to these tasks?

The late SNCC revolutionary Ralph Featherstone, A. B., and I hung out sometimes when we were all together in Atlanta. Once on the basketball court in a pick-up game, before A. B. had committed to remain South, Ralph, looking at me but talking to A. B. said, “Stone, A. B. is a poet.” His tone was a lighthearted and humorous depreciation of “art for art’s sake.” It did not demean poets or poetry, but this was the mid-sixties, “the high tide of Black resistance,” as James Forman had termed it. Now, one had to be artist and activist. One’s poetry, if connected to the struggle, to the people and to the community, would grow stronger. A. B.’s certainly did. Feather’s aforementioned statement probably had as much to do with A. B. remaining South, as did those SNCC sisters. As such, A. B. had his activism thrust upon him.

Toni Cade Bambara was born to her activism, I do believe. From the first meeting, one discerned her intensity and her passion. Toni didn’t need a nudge like A. B. She was already there.

In the mid-seventies, Toni moved South to Atlanta, which at that time had a very active political and cultural community. Some of the questions this vibrant community confronted were how to make our art relevant to the masses of people and how to make it serve the ends we were fighting for. We were all developing our activist and aesthetic frameworks out of our participation in the various social contradictions that confronted us in Atlanta.

In Atlanta, Toni was in and out of the Academy numerous times, but she was never of the Academy with its isolation and sterility. She was of “The Community” with its teeming issues and confrontations with life. Her fiction and her language cemented her bond with the community and its people. She seemed more at home founding writers’ groups and hosting writers and activists in her home.

For Toni, the truest aspect of art is its role as a social force, its ability to move people, to define a reality. One critic has observed,

Art is essentially a means of communication among men/ women through which life and consciousness are enlarged.

As it related to art, two views generally content as to art and aesthetics. On the one hand, there is the individualistic, “art for art’s sake” view that attempts to place the artist outside of a particular social context and isolate beauty and fix it in a manner that makes it its own reason for existence. The aesthetics of this view is the withdrawal of the artist from her responsibility to comment upon her social existence, and even further, to be an active part of its forward development and transformation. Toni stood at the polar opposite of this dialectic. For her, art and literature reached its highest level when one’s work attempted to transform the consciousness of the people and move that consciousness in a positive and progressive manner. Hers was a view that saw the artist as an integral part of the dynamic, moving historical process. This aesthetics is related to how successful one is in relating beauty to its role in enhancing the human condition.

The art of Toni Cade Bambara’s short stories showed us how to encounter our African American lives, how to celebrate and ennoble our culture…all of it. The novel may have been created for Toni Morrison, but certainly, the short story was created for Toni Cade Bambara. Every creative writer, at one time or another, is seduced by the novel. The siren song of “The Great American Novel” lures us all eventually. Toni Cade’s effort was The Salt Eaters, an innovative and path-breaking novel. It mirrored our great musical creation, jazz, with its improvisational techniques. However, it was the short story that suited Toni’s art best and she excelled at it. Her stories captured the here and now; they dealt with the concrete problems Black people faced. She made art with the circumstances of Black life…merged art with life and with language, burned this onto paper and hurled them out into space and time. That is the universality of Black Art.

The art of Toni Cade Bambara’s short stories showed us how to encounter our African American lives, how to celebrate and ennoble our culture…all of it. The novel may have been created for Toni Morrison, but certainly, the short story was created for Toni Cade Bambara. Every creative writer, at one time or another, is seduced by the novel. The siren song of “The Great American Novel” lures us all eventually. Toni Cade’s effort was The Salt Eaters, an innovative and path-breaking novel. It mirrored our great musical creation, jazz, with its improvisational techniques. However, it was the short story that suited Toni’s art best and she excelled at it. Her stories captured the here and now; they dealt with the concrete problems Black people faced. She made art with the circumstances of Black life…merged art with life and with language, burned this onto paper and hurled them out into space and time. That is the universality of Black Art.

Was our generation, those of us who came to maturity in the fifties and sixties, the first one to have to order the dialectic between art and activism, as if time and history and circumstance decreed that task for us? Certainly others—Langston Hughes and Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston come to mind—spoke on the question of the role of the Negro writer/artist. They raised this question as individuals, but it was the aforementioned generation that saw and acted upon the integral nature of art and activism. During Toni Cade Bambara’s generation, it was almost axiomatic that an artist would be an activist and place her art at the service of the masses of people.

This then was Toni’s generation. The Black Arts Movement and the Black Power Movement dominated the cultural and political terrain.

Social phenomena may sometimes explode before our very eyes and we are unable to discern its contours or to know its antecedents (The Negro Rural School Movement). Such certainly has been the case with our literary artists. Their numbers have expanded well beyond what one might have expected. Toni Cade Bambara is one of the people responsible for this large expansion of Black writers, male and female, published, self-published, and unpublished. Believe me, they are out there with excellent novels, short stories, biographies, poems, and non-fiction. And because of Toni and the Movement she was part of, they can be writers without the same demands placed on them for activism as that previous generation of artist-activists. However, they should and must pay homage to the aesthetic that was set forth by our bonded ancestors in their development of the African American Spiritual and that has threaded itself down through our most important cultural and political achievements (the blues, jazz, Negro Renaissance, Black Arts Movement, Black Power Movement). That aesthetic demands that our quest for truth and beauty be linked to our struggles for freedom, justice, and equality—linked to our social reality. That is another aspect of the universality that our art demands.

It was Karl Marx who said that each generation must discover its mission and either fulfill or betray it. But even before that, this maxim was put forth by the great prophetic, Negro Spiritual “We are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder” where “every round” (generation) ascends “higher and higher,” if we fulfill the requirements of our social responsibilities. The slaves’ development and creation of the African American family was arguably their greatest social achievement. Certainly, Toni, with her passion for revolution, did fulfill the responsibilities of her generation’s mission arising out of her social consciousness.

I have been an activist most of my days, and I am old enough to have lost numerous movement friends. The death of those friends and comrades has created a special sense of loss for me. It has been their passion for revolution and fundamental societal change that has marked their sojourn here and no one has filled their social or cultural space. No one can, so we miss them terribly. The emotional ache reaches down into your soul and the only comfort is the memory of them in their quest for freedom, justice, and equality. I first felt that special agony with Ruby Doris Robinson and later with Ralph Featherstone and then Ron Carter and now Toni. There are simply too many of them to name. There is a mountain of them and we need to remember them and pass those memories forward.

Toni moved to Atlanta in the mid-seventies, and I saw a lot of her at various cultural and political functions. Our daughters Naima and Karma shared an alternative learning institution. I was a member of the Southern Collective of African American Writers that she helped found. We also had a common experience in visiting socialist countries—she had traveled to Cuba and Vietnam and I had visited Cuba and North Korea. Above everything else, she was a revolutionary intellectual, intensely passionate about Black people and social change. She was also beautiful. She has those Baldwin and Baraka bubble-eyes. Those bubble eyes could blaze like lasers cutting through cant and hypocrisy. But mostly they were warm and inviting. Those same eyes run in my family, my grandmothers’ people the Johnsons. The Johnsons are full of bubble-eyed people. Toni was always a delight to talk to, full of interesting perspectives on organizing and ideas for pushing the Movement forward and she was optimistic about our future.

The axis of my life has been art and activism and I think the same axis drove Toni. Her literary art and her political activity to advance democracy for African Americans were her passions.

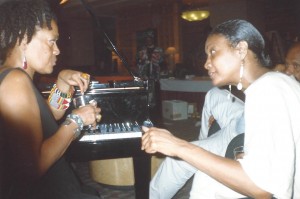

Toni moved to Philadelphia during the eighties, and I saw less of her, but our paths would cross at conferences and festivals and the like. I heard she had cancer, and I knew she was a fighter. The last time I saw her was at Atlanta’s National Black Arts Festival in 1994. This festival has always been a kind of reunion for artists and activists. We hung out, talked, danced, attended the Abbey Lincoln concert and had a great time together. Our last time seeing each other was in the lobby of the Renaissance Hotel. A piano was there and she was playing Movement songs and Amina and Amiri Baraka, Mike Simmons, and a few others of us were singing our asses off. Nya was there taking pictures. It was a great moment. That was the last time I saw Toni.

Mike Simmons, who is from Philadelphia, and I were in Budapest, Hungary in 1995. He received a call from friends in Philadelphia, and was informed that Toni had passed away. The news was not altogether a shock, but for those of us who knew her, a cloud settled over us. But then Mike and I remembered how alive and vibrant she had been in Atlanta at the Festival and how much she meant to our Movement. Her spirit will always be a beacon to artists and activists.

Eternal glory to our friend and comrade, Toni Cade Bambara.

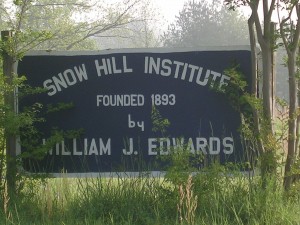

Donald P. Stone is the grandson of noted Alabama educator William James Edwards, and is a graduate of Snow Hill Institute, the school founded in 1893 by his grandfather. He is also a 1957 graduate of Morehouse College, a school headed by Benjamin E. Mays, the mentor of Martin Luther King, Jr. Edwards and Mays were instrumental in forming the intellectual and social contours of Stone’s life. Writing and social activism have been the axis around which Stone’s life has turned. He was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), The Black Workers’ Congress, and the African Liberation Support Committee. He is the author of Fallen Prince, a biography of his grandfather, and Critical Expressions, a volume of essays on politics and culture. He is considered an expert on the Negro Rural School Movement.

You may also like...

3 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Feminists We Love: Linda Janet Holmes [VIDEO] - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Toni Cade Bambara: A Woman of and for the People - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire